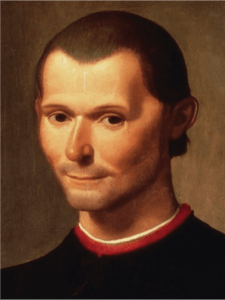

Machiavelli: The Horrors of 16th Century Diplomacy

All through the autumn of 1502 Niccolò Machiavelli has been shadowing Cesare Borgia as he fights off a major rebellion and gets ready to fight back. There have been times when the Duke has taken the Florentine diplomat into a kind of confidence. But not any more…

Winter descends, bringing wind and icy rain. But it is the drop in diplomatic temperature that makes his life particularly inhospitable. The Duke has no use for Florence any more and so he is cast adrift. Were their roles reversed Machiavelli knows he would have done the same thing.

Winter descends, bringing wind and icy rain. But it is the drop in diplomatic temperature that makes his life particularly inhospitable. The Duke has no use for Florence any more and so he is cast adrift. Were their roles reversed Machiavelli knows he would have done the same thing.

But it is not just Florence that is ignored. In the city of Iola, Cesare Borgia seems to have gone off the diplomatic game altogether. Instead he has returned to his old habit of inverting night and day, so that the only time to see him is when everyone else is in bed. There are rumours of alternating lethargy and tantrums, even a re-occurrence of the agonies of the pox. But all is conjecture.

‘You must remember that we deal with a prince who governs by himself,’ Niccolò writes home, not without certain bitterness. ‘So do not impute it to negligence if I do not satisfy you with more information, because for most of the time I do not even satisfy myself.’

There is no satisfaction to be had anywhere else either. Two months of a billeted army has eaten the city and its neighbouring land down to stalks and scrag ends. There is barely a cask of decent wine to be found and a clean woman would demand more money than he could raise, and even then she would probably be lying. He finds himself missing Marietta more than he might like to admit. But there is no solace to be gained there: from loving letters, through impatient ones – ‘you promise a few weeks and already you are gone for months,’ – she has now fallen into petulant silence, though it seems she is shouting loud enough to anyone else who will listen.

‘She misses you, Niccolò, that much is clear, though she has a strange way of showing it.’ Biagio writes. He can almost see his friend blowing on his fingers to show the heat of her anger. ‘I’ve done what I can. For God’s sake send her funds or a present of some kind to keep her sweet.’

Except he has nothing to send. He has eaten up each month’s wages and expenses before they arrive and his requests for more money are ignored. Who would be a diplomat from a modest family in Italy? Influenza stalks the city and he shivers under thin blankets as water dribbles down the inside of the walls. He finds himself thinking about his life up until now. Remembering youthful conversations with his father about the importance of a man serving the city he loves. And he had been educated to do just that. But instead, Florence had fallen under the sway of a zealot who believed that God had sent him to create the kingdom of heaven on earth. No dancing, no gambling, no fornication and worst of all, no words worth reading but the words of God. Niccolò had sinned enough during those years for a lifetime of penances, and he wasn’t the only one. By the time a new government needed new faces, he was something of an expert in human nature; both in the past and the present. But he was no longer a young man. At twenty-nine, he had had some catching up to do. And now at thirty-three he feels it even more intensely. In late November, with no more intelligence to be gleaned, and even if there was, no money to get it, he asks be recalled. The council have made their decision and he can do no more. ‘If it goes on like this you will be bringing me back in a casket.’

It does no good. His request is refused. Niccolò Machiavelli is far too good at his job to be allowed home. That night he takes himself to a tavern where he knows that other, richer envoys like to congregate to bitch about the hardships of diplomatic living. Next morning he wakes to blinding headache and the satisfaction of knowing that no one except Cesare Borgia himself has a clue what his next move will be.

This extract from In The Name of the Family: A Novel of Machiavelli and the Borgias